For many surgical procedures, the additional risks associated with patient obesity are well understood. Obesity has a clear association with a wide variety of complications developing shortly after surgery. Surgical site infections, respiratory complications, deep venous thrombosis, readmission rates and length of hospital stay are all adversely impacted upon by the presence of obesity. Despite this knowledge, the impact of obesity upon the failure and revision rate of joint replacements has been uncertain. Whilst it might be logical to think that artificial joint replacements might fail earlier with increasing load placed upon them, medical literature thus far has failed to support this hypothesis. It would appear that while obese patients are at significantly higher risk of complications around the time of surgery, the longevity of their joint replacements is relatively uneffected by their body weight.

Part of the reason why the medical literature has been unable to clearly answer the question relating to longevity of joint replacements in obesity relates to the difficulty in studying joint replacement failure in general. Modern joint replacements are exceptionally successful. They have very low failure rates and it typically takes a very long time for a joint replacement to fail. Many hip replacements designs have failure rates less than 5% at 10 years. Given the success of hip replacement procedures, designing a clinical study to detect differences in failure rates can be very difficult in design and costly to run. The number of patients enrolled in the study would need to be large, and they would all need to be followed for an exceptionally long duration of time. Many studies are therefore just simply underpowered. Whilst differences between obese and non obese people may be present in terms of joint replacement survivorship, most studies are inadequately designed to detect the effect.

To address these concerns and to enable accurate performance monitoring of artificial joint replacements, many countries have developed Joint Replacement Registries. The Australian Orthopaedic Association (AOA) established our registry in 1999, and since 2002 has been monitoring the results of all hip and knee replacements performed in this country. As of the 2018 annual report, there are almost 1.4 million joint replacements being tracked for performance in Australia. The Australian National Joint Replacement Registry (ANJRR) is widely accepted as one of the most influential and important pieces of evidence that guides joint replacement surgeons and their recommendations for surgery.

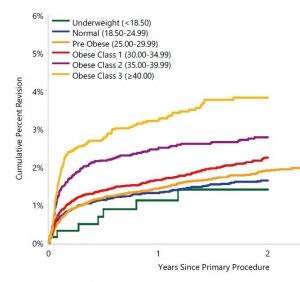

Since 2015 the ANJRR has collated information relating to patient Body Mass Index (BMI, a measure based on your height and weight) to observe difference in joint replacement performance. The registry now has body weight, BMI and outcomes data on over 85000 people who have undertaken hip joint replacement. That’s a lot of information – enough to meaningfully comment on the impact of obesity on joint replacement failure within the first 3 years of surgery.

The first observation to make is that revision rates of hip replacements increase with BMI. For all grades of obesity (BMI >30) the revision rate is statistically higher, with obesity grade 3 people (BMI >40) having a 2.47 times higher revision rate within the first 2 years of surgery.

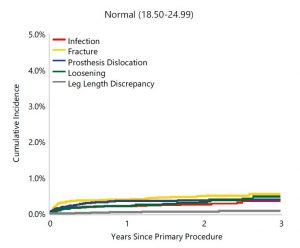

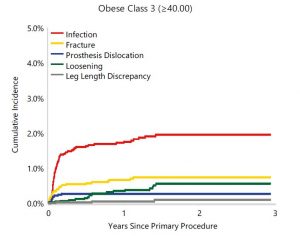

What is potentially more important however is the cause for revision. The two graphs below show causes for revision of hip replacements in people of normal weight, compared to people of obesity grade 3. The main cause for the higher rates of revision in obese people is a very substantially higher rate of infection. Arguably, infection is one of the worst types of joint replacement failures – it is commonly associated with the requirement of multiple re-operations, extended durations of treatment in hospital and long term antibiotic therapy.

Also bear in mind however that these graphs only represent the “tip of the iceberg” in terms of obesity related complication rates. They only capture revision of the implants as the outcome measure. This data does not report on a variety of other obesity related complications. For example, infections sustained without implant revision, deep venous thrombosis and respiratory complications are not captured by the ANJRR but are nonetheless still very important.

The responsibility to obtain optimal outcomes after surgery is shared between care providers and patients themselves. Obesity represents a reversible risk factor that substantially impacts upon the outcomes of hip joint replacement surgery. Weight loss can be difficult, particularly with an arthritic joint resulting in decreased mobility and exercise tolerance, but it still can be achieved. Your chances of success with weight loss efforts are significantly greater with professional assistance – speak with your doctor, dietitian or exercise physiologist and they will be more than happy to help.

This information has been written by A/Prof Patrick Weinrauch for the purposes of patient education. The details provided are of general nature only and do not substitute for professional recommendations based an individual clinical assessment. ©

A/Prof Patrick Weinrauch is an Orthopaedic Surgeon and the Director of Recovery Medical. Patrick, after repeatedly observing that better results were reliably obtained in those patients who were more optimally prepared for surgery, developed Recovery Medical to assist people in their preparation and post–surgical recovery.

The graphs within this blog are from the 2018 Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry Report. The full report and associated information is available online here.